Do you have a back to school tradition in your family? Back when I was a kid, going school shopping especially for new “school” shoes, was a big event in my family. We also did the big school supply shopping trip where my brother and sisters and I would spend an inordinate amount of time deciding on the color of our folders and notebooks.

It wasn’t until I started writing this post that I realized that my family actually does not have a similar back to school experience. We tend to buy so much on-line, that trips to the physical store are really reserved more for groceries than anything else. However, I thought it might be fun to start some sort of tradition, so I decided to take my daughter shopping for school supplies instead of just clicking the buy it now button on my computer. The result:

Me: What color folders would you like? You need 3.

My daughter: Does it matter?

Me: Um, I guess not.

My daughter: Just pick 3 then.

In other words, this is not the right tradition for my family. Undeterred, I decided to take my daughter, who is not a fashionista by any means, clothes shopping. The result:

Me: Pick out some clothes and we’ll go to the dressing room so you can try them on.

My daughter: I hate trying on clothes. (She picks up a random pair of yoga pants). These are good. Let’s go home.

OK, also not a success. So then I asked her, what do you think our family’s back to school tradition should be? Her response: We can walk to the bus stop together and you can wave to me when I’m on the bus.

Isn’t that sweet? And, sure, this probably won’t fly when she’s in middle school, but for a few more precious years, I’m all for that kind of tradition.

Speaking of back to school, your young scholar might get a kick out of the old article I found in a back issue of Ask magazine. Entitled “Way Back to School,” it’s a fascinating look at the school life of kids (well, boys mostly) starting way back in 320 BC, perfectly illustrating how some school traditions have stayed the same for thousands of years.

Way Back to School

By Tania Therien

Art by Robert Byrd

How do humans learn? They go to school, of course! School is for more than just learning your ABCs and 123s. It also teaches you the skills and values that your parents and your community think are important. Kids (well, boys mostly) have been going to school for thousands of years, but what they learned depended on when and where they lived. What about the girls? Now that women do the same jobs as men, girls and boys go to the same schools and learn the same things. But it hasn’t been that way for long. Only in the last century or so have girls been offered an equal education.

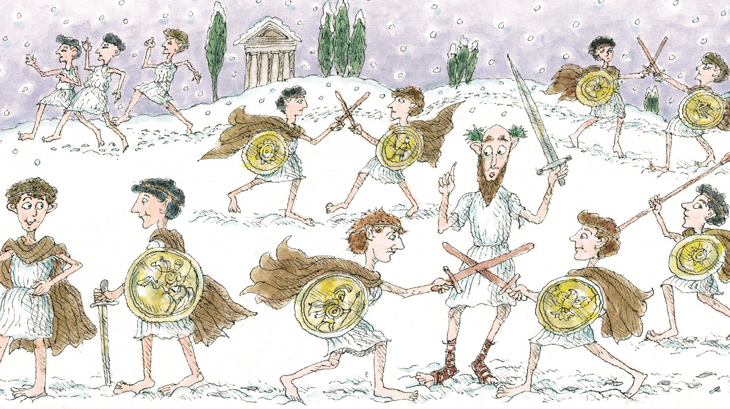

Sparta, Greece 320 BC

The city of Sparta was feared and renowned throughout the ancient world for its especially fierce warriors. All young men went to the same school and had to serve as soldiers in the Spartan army until the age of 30. Only after they finished their education and served their military time were they allowed to marry or become full citizens of the city. Sparta had only one kind of school, the agōgé. Spartan boys started school at about age seven. They learned many of the same things you learn today: reading, writing, arithmetic, poetry, dance, music, and public speaking. They also got some tough training designed to make them strong, disciplined soldiers.

According to the ancient writer Xenophon (431–354 BC), students of the agōgé were given just enough food to ensure that they wouldn’t be hungry, but never enough to be full. This taught them not to be picky, and to be able to go without, which soldiers sometimes have to do. If they were hungry, they were encouraged to steal. Yes, that’s right, steal! If a student was caught stealing, he would be severely beaten. But Spartans believed that teaching a boy to steal well, without getting caught, would make him craftier and more inventive, and give him warlike instincts.

Running barefoot was thought to make the boys quicker and more surefooted, so they were not allowed to wear shoes. And to toughen them up to face any kind of weather, they could wear only one cloak, summer or winter.

What about Girls?

Spartan girls attended a school to develop their physical skills. They ran races, wrestled, and built strength and endurance. They also joined a chorus, taught by a professional poet, where they learned music, song, and dance. At home they were taught basic reading and writing.

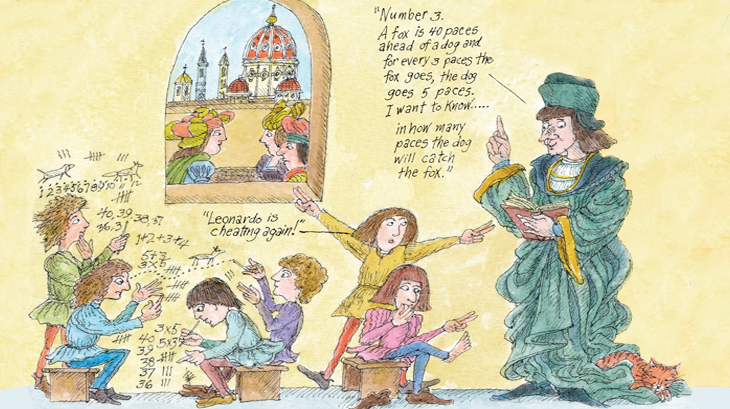

Florence, Italy AD 1450

At the height of the Renaissance, the city of Florence was the place to be. It was a thriving commercial center where many people worked as bankers, merchants, traders, builders, and artisans. What do you need to know to be really good at these jobs? Math! For a long time, schools in Florence didn’t teach math. Adults just learned the math they needed on the job. Then Florentines realized that if they taught good math skills to kids, the kids would grow up to be better at their jobs. If they were better at their jobs, the city would make more money and become more powerful.

In the 1400s, Florence had about six schools dedicated to math alone, called abbaco schools. (Abbaco means business arithmetic.) Students usually began attending the school at 10 or 11—they had to be able to read and write before starting.

In abbaco schools, boys learned finger reckoning, a kind of math sign language. They studied multiplication and division of whole numbers (memorizing multiplication tables from 1 through 20), fractions, money, weights, and measures. School went on all year for two years, starting at dawn and ending an hour or two before sunset. That meant that in the summer, students would start school at 5:00 am and study for 12 hours.

After finishing abbaco school at 12 or 13 years old, many students started working at banks or as merchants right away. Others studied more Latin, went to a university, or entered an apprenticeship

What about the Girls?

Florentine girls didn’t attend abbaco schools. But they did learn to read and write, either at home or at an elementary school with the boys.

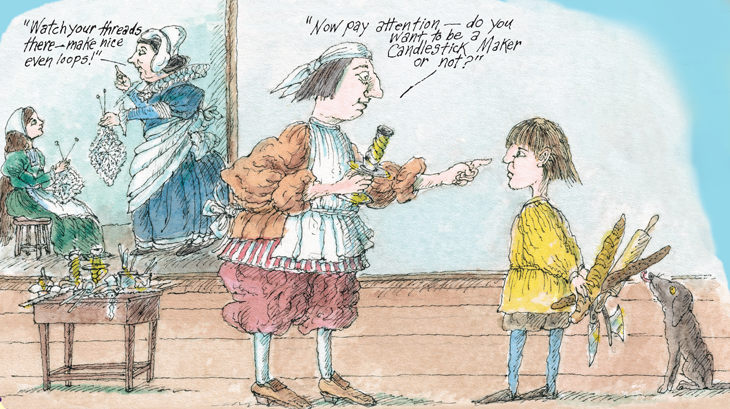

Paris France, AD 1600

For many centuries, young people have been workers in training, or apprentices. If you wanted to be a butcher, a baker, or a candlestick maker; a housekeeper, a blacksmith, or a painter; a jeweler, a tailor, or a bookbinder, or—well, you get the idea—you had to be an apprentice first. In medieval and early modern times this meant that a young person went to live with someone—a master—who was very skilled at a certain job. The parents paid the master, and the student ate, slept, and worked at the master’s house and workshop.

Most apprentices started at about 11 or 12 years of age. How long they lived and worked with a master depended on the trade they were learning. In Paris, budding cooks lived with a master for two years. Training for silversmiths took 10 years. Most apprenticeships lasted seven to eight years.

Being an apprentice wasn’t like going to school, even though apprentices spent all day learning. They started work at the same time as the adults in the shop, probably around dawn, and stopped working close to sunset. Doing simple tasks, they got to know the tools in the shop and worked their way up to more complicated projects. They learned about the rules of the trade, what prices to charge, and how to compete fairly with others in the same job. When apprentices weren’t working in the shop, they had other chores to do for their master, like fetching bread and drink. Apprentices were not paid. At best they received a bit of pocket money to spend as they wished.

Eventually, apprentices grew expert at their trade. Once their training was complete, they became journeymen, traveling and working at different shops with different masters to learn even more. And, after many years, a journeyman could apply to become a master and take on apprentices of his own.

What about the Girls?

Sometimes girls became apprentices. Often they learned from their parents, but they might also go to live with a master and learn a trade. They, too, could grow up to be crafts “men.

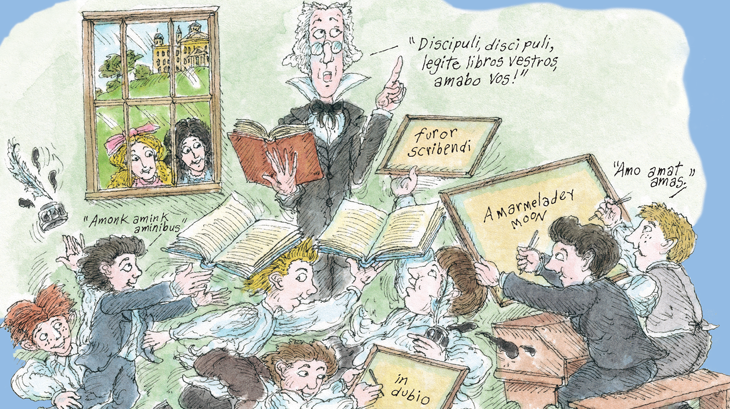

England AD 1850

In 19th-century England, parents wanted stability, safety, and tradition for their children. Those who could afford it sent their sons to private boarding schools. Except for holidays at home, boys lived at school for up to eight years. Students slept in a large dormitory room with many other boys. Classrooms were usually big assembly halls, where a number of classes went on at once.

Boarding school students learned little that would help them at work. Instead they learned Latin, Greek, ancient history, and geography. Parents believed that these studies would make their sons better people. Boys might study French, fencing, music, or dance, but little math and no science. Students interested in science paid extra for a lecturer who visited the school once every year or two.

Outside of class, prayers, and meals, students were free to do what they liked. They could play games, hunt, or hike. The older boys were put in charge and often made the younger ones do chores like polishing shoes, making fires, or cooking.

When boarding school students graduated, some went on to a university and others went straight to work. Even if life at boarding school could be lonely and difficult, some boys didn’t want to leave. Former students set up “Old Boys” clubs where they could meet with friends from school. Many of the boarding schools still exist, attended by the sons and grandsons and greatand great-great-grandsons of the Old Boys.

What about the Girls?

In 1853, 58 young ladies attended Cheltenham Ladies’ College, a private boarding high school, to study music, sewing, and drawing. Today 850 girls attend Cheltenham, and nearly all of them go on to a university to study medicine, law, and everything else.

For more stories like these, be sure to subscribe to a Ask!