One of the worst things I’ve ever done in my life was to laugh at my husband when he told me about an idea he had. He had imagined a door mat that had some sort of automatic trigger in it, so that when it felt weight, it would ring a doorbell. This would be the solution for our outdoor cats, who scratched up our front door upon returning from their meanderings, and also for our dog, who annoys our neighbors by becoming completely and utterly panicked, loud, and howl-y if we don’t immediately run to let him in the very first time he barks.

I completely understand where this idea came from, and in many ways it makes a lot of sense. But at the time, all I could think about was the CONSTANT chiming of this doorbell. Not only from our own pets, but from kids, neighbors, the mailman, the salespeople, the skunks and raccoons who live in our neighborhood… So I told him it was a terrible idea and crushed his spirit. Luckily, my husband is a 40-year-old adult who didn’t take it to heart. Or at least he’s finally (in the last few months) managed to drop the grudge he was carrying about it for the last eight years.

However, as our kids head back to school, to the wonderful world of science fairs, Odyssey of the Mind, and other innovative programs that encourage creative inventions, this story serves as a healthy reminder to support our kids in any and all ideas, suggestions, or improvements they might bring before us.

Kids have wildly fanciful ideas and it’s really easy to dismiss them. But, as evidenced here, discouraging ideas can be detrimental, with long-term consequences for their willingness to think outside the box or to enlist you as an ally in their creative and intellectual development. If your kids are chatting about ideas to procrastinate, or you simply can’t deal with it at the moment and need to redirect, encourage them by saying the idea sounds good and suggest they write it down to discuss later. Then, when the time is right, and the algebra is done, talk it through with them, posing all the potential pitfalls in a “how will you solve for X?” manner, and see how they can come up with ways to solve each question. Embolden your kids to work through and realize each invention or idea with the problem-solving skills, the creative thinking, and the innovation that adults seem to lose after a certain number of years dealing with the constraints of reality.

In the spirit of inspiring inventive thinking, below you’ll find an article from Cobblestone called “Steam’s Evolving Engine”, which traces the development of the steamboat, whose final rendition in the 1800s was actually the result of centuries of hard work by a number of inventors. The next time your child (or even your husband) comes up with an idea that still needs a bit of tweaking, we hope you’ll share this article to remind the inventor that it’s OK to think outside the box.

The fact is, that one new idea leads to another, that to a third, and so on through a course of time until some one , with whom no one of these ideas is original, combines all together, and produces what is justly called a new invention. –Thomas Jefferson, March 3, 1818

Steam’s Evolving Engine

By Mimi Boelter

History books tend to connect just one person’s name with the invention of a remarkable new machine or the discovery of a new technology. But, the reality behind new ideas usually presents a different, and more complicated, picture. A good example of this is the steamboat, whose final rendition in the 1800s actually was the result of centuries of hard work by a number of inventors.

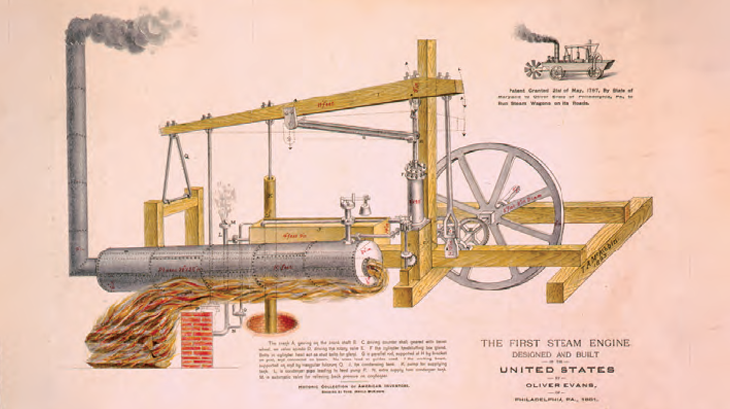

When water is turned into steam through the use of heat, it expands. This conversion produces force that provides the power for steam engines. And it was the correct combination of steam, pistons, and cylinders that led to the successful creation of the steam-powered engine. The following inventors all contributed to that end result.

Hero, a first-century Greek inventor, came up with the aeolipile, which harnessed steam power by using a metal sphere that turned on its axle above boiling water. In 1698, Englishman Thomas Savery produced the first steam-powered machine. Called the “Miner’s Friend,” it was a water pump that, unfortunately, often exploded.

In 1712, Thomas Newcomen, also English, invented an engine that used steam to push a piston that, in turn, drove a pumping mechanism. Employing low atmospheric pressure rather than the high steam pressure required by Savery’s engine, the Newcomen engine did not blow up easily and was used for decades to pump water out of mines all over Europe.

As the demand for industrialized products increased later in the 1700s, the need for more reliable and consistent power grew. Textile and grain mills had been dependent on nearby water sources to turn the wheels that supplied the power. And because of this dependency on water, the mills were forced to shut down in times of drought or flooding. Steam engines eliminated these problems.

James Watt spent 20 years developing a steam engine based on Newcomen’s model. From about 1764 on, Watt improved the Newcomen engine in several ways. Watt’s double-acting engine forced steam into the cylinder above the piston to create a downstroke, and then below it to create an upstroke. This double action drastically reduced the time it took for the piston to return to its original position and created power in both directions. Watt also employed steam pressure. Instead of having steam force water up into a reservoir and onto a water wheel, Watt’s engine used steam to move pistons that turned the axle of the water wheel.

“Sun-and-planet gearing” allowed the steam engine to create a rotary action, which is essential for continuous forward movement. The “planet,” a toothed wheel connected to the end of a rod, rotated around the “sun,” which was a gear whose teeth interlocked with that of the planet’s. Although a Watt employee named William Murdoch actually invented the sun-and-planet gearing, Watt patented the design in 1781.

Watt had developed an engine that worked more efficiently using less steam. In his version, a set amount of steam filled a longer cylinder than in the older engine, so the steam was allowed to expand to twice its original volume, providing about 70 percent more work capability.

In 1786, a new boiler design by James Rumsey further improved the effectiveness of the steam engine. He invented a pipe boiler to replace the old, cumbersome one. Rumsey’s boiler consisted of a thin tube that was twisted and spiraled up to the engine. Using less fuel, his creation allowed water to get hotter in a shorter amount of time.

John Fitch began building steamboats in 1786. With his development of a longer cylinder in 1787 came yet another contribution to the steam engine. The following year, Fitch and his partner, Henry Voigt, built a 60-by-8-foot boat. Using a 12-inch cylinder and Rumsey’s pipe boiler, they lightened the boat’s load. Four oars mounted on the stern provided the propulsion system that pushed their boat 20 miles upriver from Philadelphia to Burlington, New Jersey. To that date, this was the longest nonstop trip made anywhere by a steamboat.

Fitch’s Steamboat Company ran America’s first commercial steamboat service. The business did not profit, however, because the costs of operating a steamboat still ran higher than that of a horse-drawn stagecoach. It would be almost two decades before Robert Fulton installed paddle wheels on both sides of the first successful steamboat and chugged up New York’s Hudson River.

From Newcomen’s water-pumping engine to Fitch’s longer cylinder to Fulton’s combination of the different improvements, it is obvious that many creative minds brought the successful steam engine to fruition. And with the dawn of the efficient steamboat came remarkable changes in transportation and industry.

Eight years later, Cricket Media Mama still feels guilty about rejecting her husband’s million dollar As-Seen-On-TV Pet Doorbell Mat idea. Maybe if biometrics can be incorporated so only certain pets trigger the doorbell… Uh, patent pending!