When I was still in elementary school, I read a mind-blowing book about girls and women who changed the world, from poets to politicians, authors to athletes. I ran downstairs and asked my mother, “Why didn’t we learn about any of these people in school?” Kids can probably name Harriet Tubman, Sacagawea, Eleanor Roosevelt, and more awesome examples of women in American history, but then there are the women who made history in a quieter sort of way. They stand as milestones and role models in their fields but probably don’t appear in your daughters’ history textbooks. Is your daughter a budding doctor or oceanographer or pilot? See if they’ve heard of any of these famous firsts!

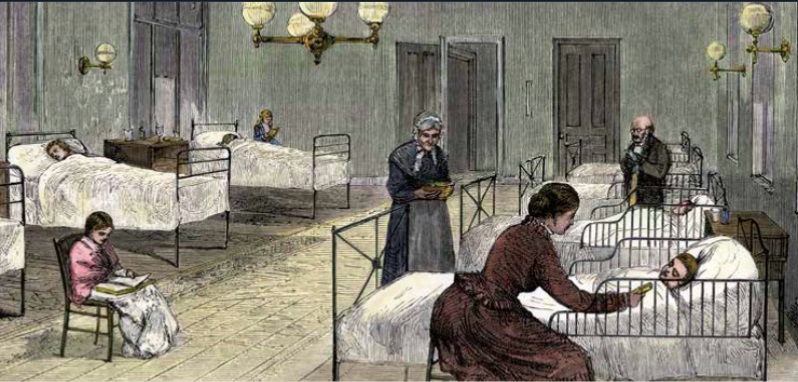

Elizabeth Blackwell: America’s first woman doctor

Back in the 1830’s, there were a lots of things that American women couldn’t do. They couldn’t vote, they couldn’t serve as lawyers, they couldn’t play professional sports, and they DEFINITELY couldn’t become doctors.

Elizabeth Blackwell, who was originally born in England in 1821, was an unlikely choice to become the first female doctor. For one, blood made her queasy. But when Elizabeth was 24, she visited a friend named Mary who suffered from cancer. Mary told her, “If I could have been treated by a lady doctor, my worst sufferings would have been spared me.” Those words set off a spark in Elizabeth’s mind that she couldn’t shake.

Elizabeth was rejected by 28 different medical schools until she finally received the letter that changed her life: an acceptance letter from Geneva Medical School in upstate New York! She didn’t know at the time that the professors had let the students vote on whether or not a woman should be admitted. They voted yes—as a joke!

But Elizabeth’s passion was anything but a joke. She graduated in 1849 with the highest grades in the whole class and the honor of being the first woman in American history to attend medical school. She also published the first medical article by a female student, founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, and helped organize nurses during the Civil War. Her former campus now displays a statue honoring her. Who’s laughing now?

Elizabeth Blackwell’s story appears in the May/ June issue of CLICK Magazine.

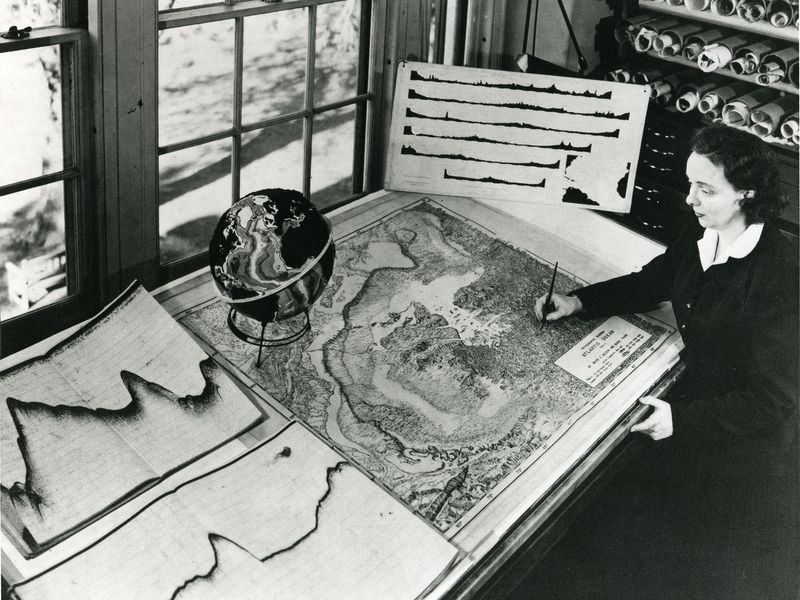

Marie Tharp: the woman who mapped the ocean floor

When Marie Tharp was a little girl, she loved tagging along with her father, a surveyor for the Department of Agriculture who tested soil and drew planting maps for farmers. She dreamed of following a similar path, but she knew that women in the 1940’s rarely got to do work in the sciences. Little did Marie know that one day she would create maps that would change the way we view the ocean forever!

Although her college degrees were in music and English, her true interest lay in geology. While at school, she took a class in drafting, or technical drawing. She was accepted into a Master’s program for geology at the University of Michigan because most men at the time were away fighting in World War II.

Marie got a job working as a ‘human computer’ for scientists at Columbia University who were studying the ocean floor. She took information from fathograms (jagged graphs of ocean depths determined by ships’ sonar) and turned it into two-dimensional drawings. It was not exciting work. She wasn’t even allowed onboard the male scientists’ expeditions because superstition held that women were bad luck on ships.

When Marie taped six large drawings of the North Atlantic together, however, she discovered something startling: a deep crevice in the middle of each profile. She had proved the existence of continental drift. Now she was inspired. Her superiors asked her to sketch a map showing the topography of the entire ocean floor, depicting the mountains and canyons beneath the waves, including the Great Rift Valley.

The work was published in a scientific paper in 1956, but Marie’s name did not appear. Only the male researchers were credited. She didn’t receive attention for her incredible work until a painter re-created Marie’s maps for National Geographic magazine in 1968. In an article for the May/June issue of MUSE Magazine, Marie is quoted as saying, “I worked in the background for most of my career as a scientist, but I have absolutely no resentments… Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge… that was something important. You can only do that once.”

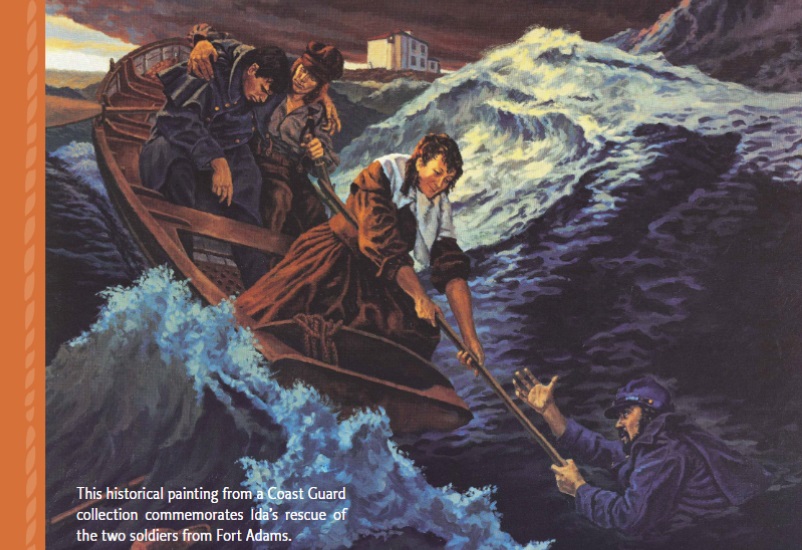

Ida Lewis: the bravest woman in America

Like Marie Tharp, Zoradia “Ida” Lewis grew up helping her father with his work. Captain Hosea Lewis was the keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island from the time it was built in 1854. After Captain Lewis suffered a stroke and became confined to a wheelchair, it was up to Ida and her mother to tend the lighthouse lamp.

Ida grew up hearing the story of a lighthouse keeper’s daughter named Grace Darling who rescued eight shipwrecked people in England, but she never thought she could do anything so extraordinary. She thought wrong. Over her time working at the lighthouse, she saved 18 lives.

The rescue that made her a national heroine, however, took place in 1869. As she gazed out the window of the lighthouse, she saw a boat turned on its side, two men clinging on for deal life. Ida, who barely weighed 100 pounds, rowed a lifeboat over the rough seas and pulled the men on board with the aid of a pole. She later learned that the men she had saved were US soldiers, Sergeant James Adams and Private John McLaughlin.

The news spread to newspapers and magazines around the world, and Harper’s Weekly magazine put a drawing of her on the cover, calling her the ‘Newport Heroine.” Famous people ranging from Civil War Generals to suffragettes to Vanderbilts met Ida and asked her for an autograph.

Even President Ulysses S. Grant asked to meet her! Although Ida offered to meet him on the mainland so that he wouldn’t ruin his shoes on the soggy island, he said, “To see Ida Lewis, I’d get wet up to my armpits.” Ida became the first woman in American history to win the American Cross of Honor. The US Coast Guard named a search and rescue ship the Ida Lewis after her, and Lewis Drive in Arlington National Cemetery is named for her—the first to honor a woman.

You can read Ida’s incredible story in the April issue of CRICKET Magazine.

Jerrie Mock: the woman who flew around the world.

Who was the first woman to fly around the entire world? If you said Amelia Earhart, you wouldn’t be quite right. Although Earhart attempted that historic flight, she disappeared over the Pacific Ocean before completing the journey. The first woman in American history to fly around the world was Geraldine “Jerrie” Fredritz Mock, who finally completed the trip in 1964.

Jerrie was the only girl at her high school to take an Engineering class. After marrying a pilot, Russell Mock, she took flying lessons and earned a pilot’s license in 1958. Her motivation to fly around the planet wasn’t to achieve a historical first but simply “to see the world.” Piloting a single-engine plane called the Spirit of Columbus (or, affectionately, Charlie), she departed from Columbus, Ohio on March 19 and returned 29 days later. She narrowly beat another female pilot, Joan Merrium Smith, who completed her journey about 25 days later.

Along the way, Jerrie made 21 stopovers and traveled over Morocco, Vietnam, Bermuda, and many more fascinating locations, which she described in her book, Three-Eight Charlie. She made the entire flight wearing a long skirt and high heels; although she preferred pants, Jerrie felt that she would be more ‘socially acceptable’ in more feminine clothes.

Shortly after she arrived home, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded her the Federal Aviation Agency Gold Medal, and she also received the Louis Bleriot Silver Medal, making her the first woman to do so. A street is named after her near Columbus, where she began and ended her famous flight. Jerrie never flew the Spirit of Columbus again, but it now proudly hangs in the Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum, not far from our Cricket Media DC office!

The March issue of COBBLESTONE Magazine focuses on Amelia Earhart but also tells the stories of several other astonishing female American aviators!

For every famous ‘first’ in history, there are countless others who follow in their footsteps. Nowadays, it’s not unusual to have a woman doctor or pilot. Reading about these four outstanding women is a shocking reminder of how much has changed in the last few centuries– and how courageous women have always existed! What mark will our readers make on the world?